Friday, January 18, 2002, Page 1.

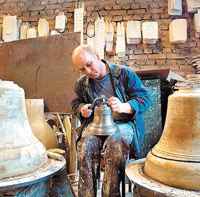

Putting the Music Back in Bell Towers

By Alexei Vladykin

The Associated Press

KAMENSK-URALSKY, Ural Mountains -- On the November day when Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev was buried back in 1982, priests say the Kremlin ordered every church bell in the country to be rung in remembrance. It would have been an impressive sound, if not for one thing: Most of the bells were gone -- victims of the Communist Party's long campaign against religion. With the religious revival since the Soviet Union broke apart a decade ago, bells are again in demand in Russia. A few enterprising metal workers have stepped in to fill the market niche and the empty bell towers. As the bells ring out their melodious chimes, the bell-makers ring up profits. Nikolai Pyatkov recalls being fascinated by an article he read about the history of bell-casting in a magazine in 1984. At the time, he and his younger brother Viktor worked as metal casters in a factory in the town of Kamensk-Uralsky in the Ural Mountains. "I started to gather literature on the subject, and my brother and I tried to experiment with different molds in a shed, but we were afraid to do it in the open," says Pyatkov, 42. Though some churches functioned during the Soviet era, many were torn down after the 1917 Revolution. Others were destroyed during the fighting in World War II, never to be restored. Even where churches were left standing, the bells were often removed. They were melted down to provide metal for power cables, tractor parts and other industrial items. By some estimates, 99 percent of Russia's bells were destroyed in the Soviet era. In 1989, after restrictions on religion were relaxed, the Soviet Cultural Foundation printed an ad in a newspaper asking for help casting bells. The enterprising Pyatkovs offered their services. Today, their company employs eight people and produces bells for 50 to 60 churches around the country each year. Their rented premises have become a bit tight, so they've taken a 2 million ruble ($67,000) loan and begun work on their own factory. No matter how big the plant, church bells can't be produced on an assembly line, since subtleties of size and shape determine a bell's tone. "A good sound from a bell depends, first of all, on the quality of bronze," Pyatkov said. "A strike of the clapper should produce a powerful sound followed by a long, velvety hum." In Russia, each parish has a unique, traditional melody, often associated with the history of the church or the town where it is located. When buying bells— which vary in size from about 50 kilograms to 1.5 metric tons— churches order specific combinations to recreate those melodies. On average, churches have 20 to 25 bells. The job of ringing the bells is often left to theological students or other volunteers. At the Cathedral of the Transfiguration in the nearby city of Yekaterinburg, the Russian Orthodox diocese is considering establishing a bell-ringers' school to help preserve the proper technique. Despite the often joyous and lighthearted sounds of bells, producing them is not easy work. Sergei Dneprov, director of a Yekaterinburg bell company that competes with the Pyatkovs, recalls how one priest argued over the price. Dneprov, a historian who collects bell lore such as the Brezhnev story, brought the priest to see the gas furnace in the casting shop. When his beard began to crackle from the heat, the priest gave in. "I can see it's hell's work," Dneprov quotes him as saying. "Give me the bill."

|